Welcome to this week’s Tip of the Hat!

Visiting a website almost always means that you will be tracked. Be it a cookie, or a script, or even an access log on the server that hosts the site, you will leave some sort of data trail for folks to collect, analyze, and use. However, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to track all the ways (pun semi-intended) a website is keeping tabs on you. What trackers should you be worried about the most? Which trackers should you allow in your browser? Are there any trackers that might track you even when you leave the site?

The Markup published Blacklight, the latest tool in the suite of tracker detection tools that allow users to discover the many ways a website is tracking users and collecting data in the process. In all, Blacklight reports on major tracking methods, including cookies, ad trackers, Facebook tracking, and Google Analytics. Blacklight also checks to find out if the website is taking your digital fingerprint on top of logging your keystrokes or session. The creators of the tool blogged about their development process, for those who want to nitty-gritty technical details on the development of the tool and how it works.

One unique feature of Blacklight is giving the user the ability to find out how a website tracks without having to visit the website. This is nothing new for folks who can write a script; however, Blacklight makes this process much easier to achieve for the majority of users who are otherwise visiting website after website to investigate how each website is tracking them. One example would be libraries performing privacy audits or reviews on library or vendor websites. Instead of having to potentially expose the worker to various tracking methods while auditing or dealing with different browsers and their settings during the auditing/testing process, the worker can work from a list of URLs and stay on one tab in their browser of choice.

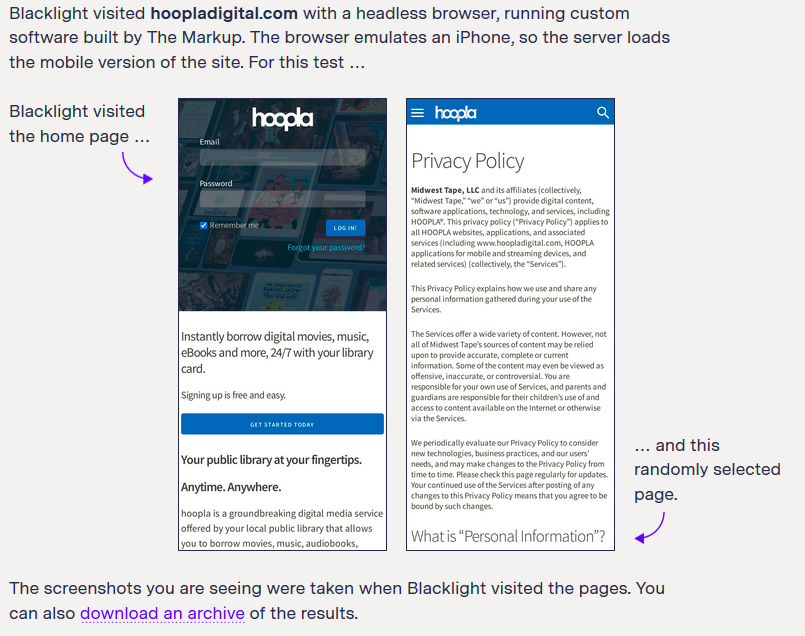

There are some drawbacks if libraries want to use Blacklight as their main tracker detection tool. As mentioned above, Blacklight tracks major tracking methods, but the resulting report does not give much information beyond if Blacklight found something. Let’s take Hoopla for example. We entered the main site URL – www.hoopladigital.com – and Blacklight visited a random page…

This is what Blacklight found:

- Three ad trackers

- Facebook tracking

- Google Analytics cross-site tracking

- Session logging (as well as possible keystroke logging)

However, the report only tells the user that these trackers are present. There is no information in the report about how to prevent session logging or blocking ad trackers. Instead, the user will need to go elsewhere for that information. The tool creators did create a post for users wondering what to do with the results, but this information is not front and center in the report.

Another drawback is that several library vendor URLS might not be able to be checked due to proxy or access restrictions. Let’s say you want to test https://web-a-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.spl.org/ehost/search/basic?vid=1&sid=e58a91f5-4f12-4648-991f-4bdc9ff8f94b%40sdc-v-sessmgr01 – the link to access an EBSCO database for a local public library. Blacklight will try to visit the website but will be stopped at the EZproxy login page every time. There is a possible way to work around this limitation by taking the source code from the two Blacklight Github repositories and reworking the code to allow for authentication during the testing process. However, it might be simpler for some libraries to visit the individual site with tracking detection and blocking browser add-ons, such as Privacy Badger, DuckDuckGo Privacy Essentials, and Ghostery.

Despite these drawbacks, Blacklight is useful in illustrating the prevalence of tracking on major websites. Library workers might use Blacklight alongside other tracking detection tools for privacy audits, provided that the library workers know the next steps in interpreting the results, such as comparing what they found to the privacy policy of the vendor or library to determine if the policy reflects reality. The tool would also be a welcomed addition to any digital literacy and privacy programming for patrons to demonstrate how websites can track users, even when a user leaves the website. Blacklight will most likely have updates and new features since the code is freely available, so it might be that some of these drawbacks will be addressed in an update down the road. But enough talking – take Blacklight out for a spin! First destination – your library’s homepage. 😉