Last Wednesday’s attempted insurrection at the US Capitol left many in various states of shock, despair, anger, and grief. As the fallout from the attempt continues to unfold, we are starting to learn more about the possible cybersecurity breaches that resulted from the attempt. Cybersecurity professionals, who are still trying to investigate the extent of the damage done by the SolarWinds attack weeks before, are now trying to piece together what could have been compromised when the mob entered the building. Stolen laptops and other mobile devices, unlocked desktop computers, paperwork left on desks – the immediate evacuation of congresspeople and workers meant that the mob had potential access to sensitive or confidential information as well as sensitive internal systems.

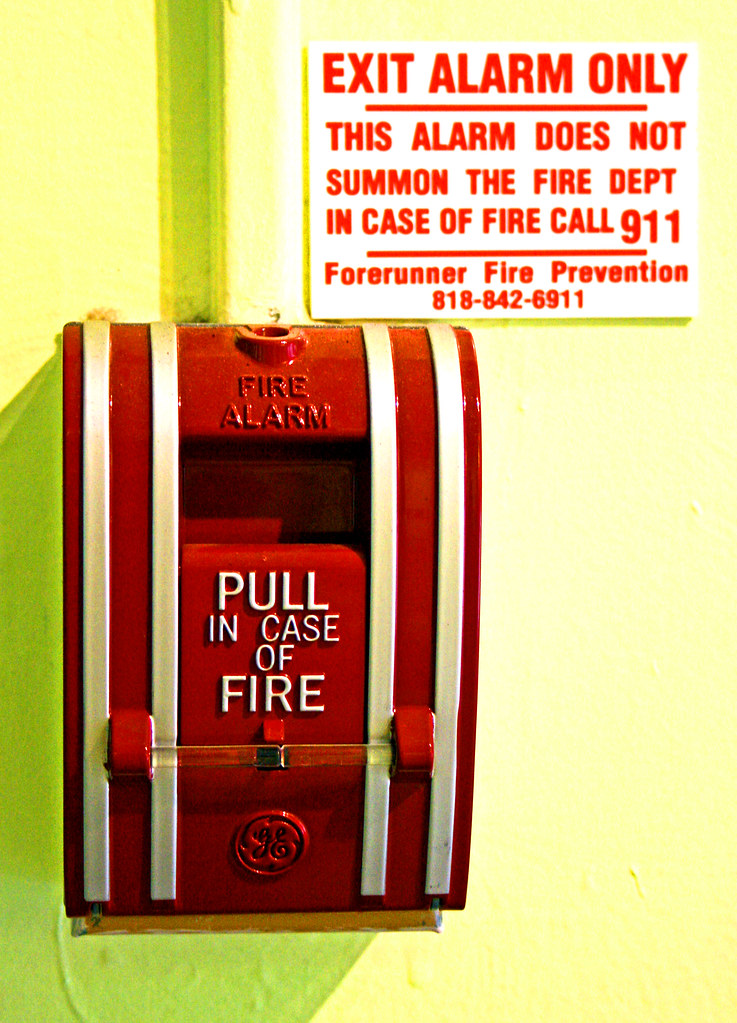

Leaving a desk, office, or service point immediately to get to safety is a real possibility, even for libraries. Active shooter training has become standard for many US organizations, joining common fire and severe weather drills where staff leave their workstations to head to safe areas. Other library workers have personal experience leaving their work station to get to safety; in one instance, someone I knew barricaded themselves in a work office with other library staff after a patron started attacking them at the information desk. Physical safety comes first. Nonetheless, this leaves information security and privacy professionals planning on how to mitigate the risk that comes with potential data and security breaches in these life-threatening emergencies.

Incident response planning and several cybersecurity strategies help mitigate risk during emergencies where staff immediately leave work areas. Preventative measures can include:

- Encrypting hard drives on computers and mobile devices

- Requiring multifactor authentication (MFA) for device and application access

- Installing remote wipe software to wipe devices if they are reported missing or stolen

- Not writing down passwords and posting them on computer monitors, keyboards, desks, etc.

- Conducting an inventory of library staff computers and mobile devices (tablets, phones, etc.)

- Setting up auto-lock or auto-logoff on staff computers after a few minutes of inactivity

- Storing confidential or sensitive data in designated secured network storage and not on local hard drives or USB drives

- Limit access to systems, applications, and data through user-based roles, providing the lowest level of access needed for the user to perform their daily work

- Storing mobile devices and drives as well as sensitive paper documents in secured areas when not in use (such as a locked desk drawer or cabinet)

After the emergency, an incident response plan guides the process in responding to potential data breaches: containing the damage, removing the attacker from doing more damage, and how to repair the damage. The incident response plan also provides communication plans for users affected in the breach as well as any regulatory obligations for reporting to a government office or official.

All of this will involve a considerable amount of resources and time; however, the time spent in planning and in training (think the tabletop exercises mentioned in our post about gaming in cybersecurity training) will be less time spent after the fact where emotions and stress are running high, resulting in things being missed or falling through the cracks after the emergency.