People sometimes ask what keeps privacy professionals up at night. What is that one “worst-case scenario” that we dread? Personally, one of the scenarios hanging over my head is insider threat – when a library employee, vendor, or another person who has access to patron data uses that data to harm patrons. A staff person collecting patron addresses, birthdays, and names to steal the patrons’ identities is an example of insider threat. Another example is a staff person accessing another staff’s patron records to obtain personal information to harass or stalk the staff member.

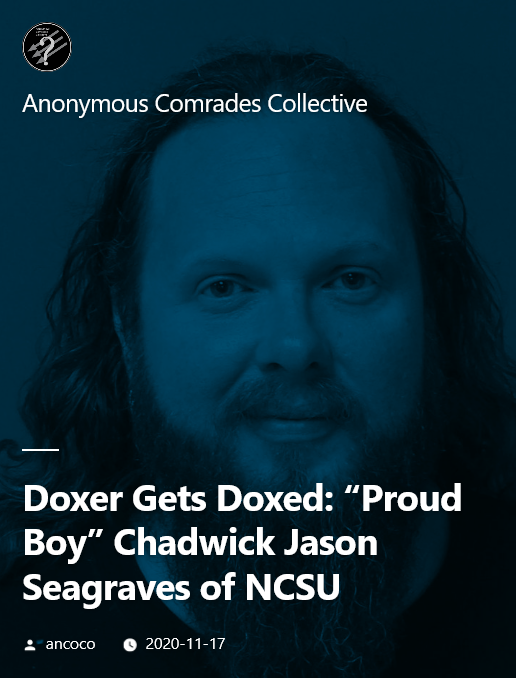

Last week, an IT employee at NCSU was doxed as a local leader of a white supremacist group. This person, who worked IT for the libraries in the past, doxed individuals, including students in his own university, to harass and, in some cases, incite violence toward the people being doxed. As an IT employee, this person most likely had unchecked access to students, staff, and faculty personal information. It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that he still had access to patron information, given his connections to the library and his IT staff position.

Libraries spend a lot of time and attention worrying about external threats to patron privacy: vendors, law enforcement, even other patrons. We forget that sometimes the greatest threat to patron privacy works at the library. Library workers who have access to patron data – staff, administration, board members, volunteers – can exploit patrons through the use of their data for financial gain in the case of identity theft or harm them through searching for specific library activity, checkouts of certain materials, or even names or other demographic information with the intent to harass or assault. The reality is that there might not be many barriers, if at all, to stop library workers from doing so.

The good news is that there are ways to mitigate insider threat in the library, but the library must be proactive in implementing these strategies for them to be the most effective:

Practice data minimization – only collect, use, and retain data that is necessary for business operations. If you don’t collect it, it can’t be used by others with the intent to harm others.

Implement the Principle of Least Privilege – who has access to what data and where? Use roles and other access management tools to provide staff (and applications!) access to only the data that is absolutely needed to perform their intended duty or function.

Regularly review internal access to patron data – set up a scheduled review of who has what access to patron data. When an employee or other library worker/affiliate changes roles in the organization or leaves the library, develop and implement policies and procedures in revoking or changing access to patron data at the time of the role change or departure.

Confidentiality Agreements For Library Staff, Volunteers, and Affiliates – your privacy and confidentiality policy should make it clear to staff that patrons have the right to privacy and confidentiality while using library resources and services. Some libraries go further in ensuring patron privacy by using confidentiality agreements. These confidentiality agreements state the times when patron data can be access and the acceptable uses for patron data. Violation of the agreement can lead to immediate termination of employment. Here are some examples of confidentiality agreements to start your drafting process:

- Heartland Community College Library

- Mesa County Libraries

- Nanuet Public Library

- Hudson Area Association Library

Regularly train and discuss about privacy – ensure that everyone who is involved with the library – staff, volunteers, board members, anyone that might potentially access patron data as part of their role with the library – is up to date on current patron privacy and confidentiality policies and procedures. This is also an opportunity to include training scenarios that involve insider threat to generate discussion and awareness of this threat to patron privacy.

A note about IT staff, be it internal library IT staff or an external IT department (campus IT, city government IT, or another form of organizational IT) – Do not automatically assume that IT staff are following privacy/security standards and policy just because they are IT. Now is the time to discuss with your IT connections about their current access is and what is the minimum they need for daily operations. However, even if the IT department practices good security and privacy hygiene (such as making sure they follow the Principle of Least Privilege), any IT staff member who works with the library in any capacity must also sign a confidentiality agreement and be included in training sessions at the very minimum.

A data inventory is a good place to start if you are not sure who has access to what data in the library. The PLP Data Privacy Best Practices for Libraries project has several templates and resources to help with creating a data inventory, assessing privacy risks, and practical actions libraries can take in reducing the risk of an insider threat.

Libraries serve everyone. We serve patrons who are already at high risk for harassment and violence. Libraries must do their part in mitigating the risk that insider threat creates for our patrons who depend on the library for resources and support. Otherwise, we become one more threat to our patrons’ privacy and potentially their lives or the lives of their loved ones.