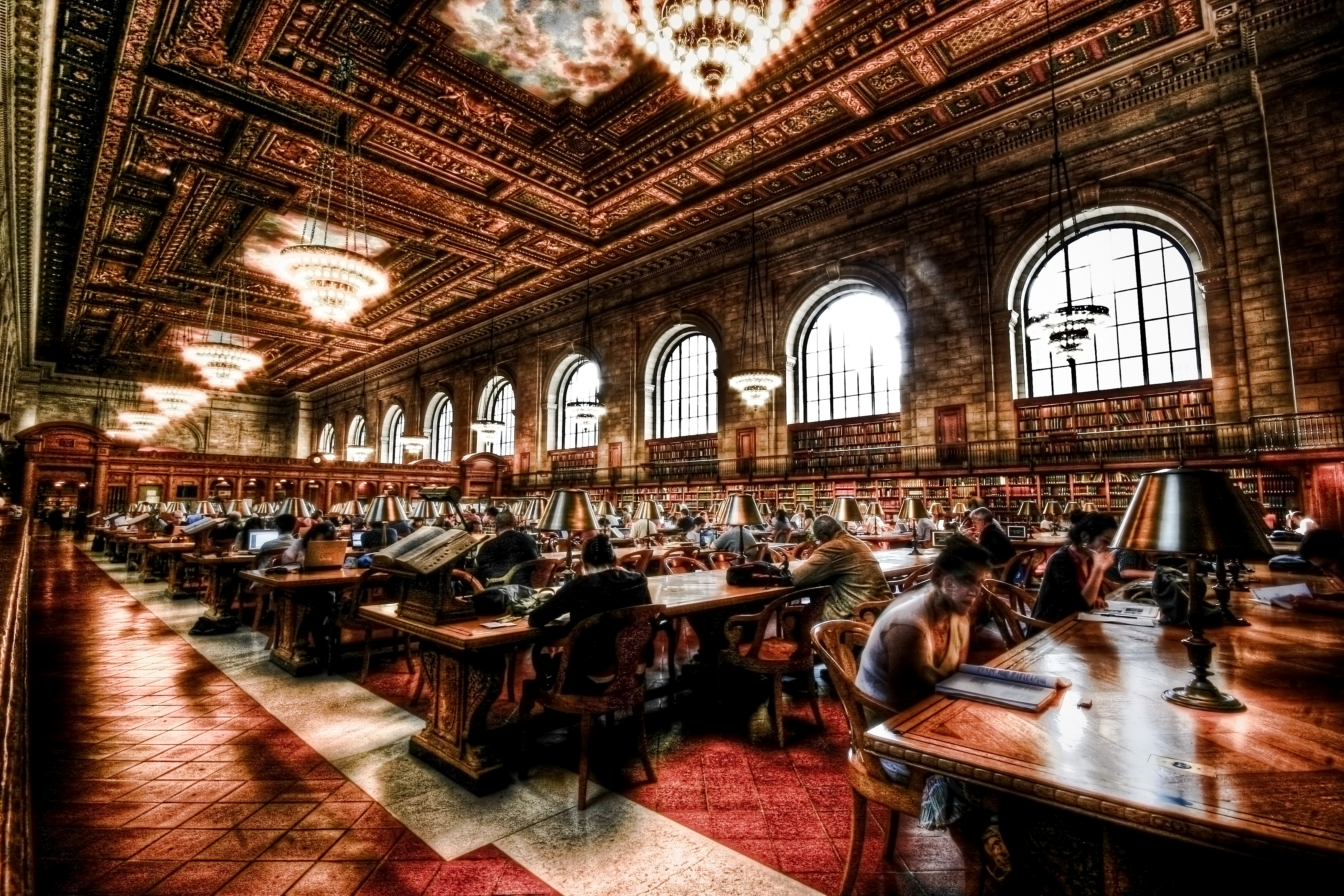

We sometimes like to say that something happens because of “magic” – in reality, that “magic” is the result of the (invisible) labor of real and unmagical people. To some patrons, this “magic” takes the form of the many programs, resources, and services the library provides daily. It takes the work of people in both the public and back-office spaces of the library. What happens, then, if you take the “magic” created by people and replace it with the “magic” of technology?

Last month the Santa Monica Public Library announced their plans to reopen a branch closed to the public due to staff cuts last year. The branch opening wasn’t made possible by regaining staff positions but instead made possible through a state grant to expand physical services through a suite of self-service technology. This grant uses existing technologies that many libraries use, including self-checkout machines, security cameras, and a controlled entry card swipe/tap or keypad. Combining these technologies to create a self-service library without staff isn’t new, either – for example, several European libraries expanded physical library hours through self-service technologies. The technology behind Santa Monica Library’s branch reopening, Open+, has been piloted in other US libraries such as Gwinnett County Public Library to expand library hours and service sans on-site staff.

This open library model comes with tradeoffs that leave many library workers worried. Library workers and patrons alike raised valid concerns around open libraries replacing staff to save costs. Another tradeoff that some might miss is the increased collection, processing, and retention of data generated from patron use of the physical library. While the individual technologies are not new, the combination of existing technologies to create an open library expands the amount of surveillance and data collection to a level that exponentially exposes patrons to various privacy harms.

We might as well start with the elephant in the room. The use of security cameras in libraries has been contested throughout the years, with libraries trying to balance using cameras for physical library security and patron privacy. ALA created guidelines about security camera use for libraries but the use of cameras in library spaces brings the risk of violating patron privacy throughout each stage of the patron data lifecycle:

- Collection – where are the cameras located? Are they recording footage of patrons using library resources, such as browsing shelves, computer usage, or other identifiable usages of materials in the library?

- Storage, retention, and deletion – where is the recorded footage being stored? Is it locally stored in the library? If not, where is that storage? Is it with a vendor, organizational IT, or even local law enforcement? How long are recordings kept? How many copies, including backups, exist, and how long are they kept?

- Access and disclosure – who has access to the footage? Library workers, the vendor, the parent organization? Can law enforcement access the footage without a court-issued order? What are the policies around disclosing footage?

Depending on the library’s location, some state and local regulations around library privacy can potentially include security camera footage as part of their definition of protected patron data. However, this protection cannot be guaranteed even if the regulations include such footage if the vendor recording and retaining footage is not legally obligated to protect this footage or if the footage is stored and retained by law enforcement.

The use of controlled entry technology brings another privacy risk to patrons in an open library setting. Academic, school, and other special libraries might be familiar with using card swipe or tap machines that control access to physical library spaces. These technologies are uncommon in public libraries, however.[1] These controlled access systems can create logs of patron data: who came into the library at what time. This patron log can potentially put patron privacy at risk through a data breach or misuse through secondary use (the reuse of data collected for another purpose) in the form of learning analytics and marketing campaigns.

Security cameras and controlled entry onto themselves create some privacy risks; nonetheless, these risks can be mitigated if particular care is put into the planning and implementation of each technology. Pairing these technologies with other monitoring technologies creates a profile of a patron’s library use through the combination of data sets. Who is doing the data collecting, storing, and retaining determines the level of risk to patron privacy. That is where libraries considering open library models need to spend considerable time assessing the privacy risks associated with who controls the surveillance technologies used to collect and store patron data. Currently, open library models consist of third-party technologies and services to coordinate all of these technologies. These third parties are not subject to state and local regulations around library data privacy (outside of California and Missouri). Trying to replace one “magic” (people) with another (technology services provided by a third party) doesn’t get rid of cost. Instead, it transfers and transforms it to the point where some library workers might not realize that the open library “magic” comes at the cost of patron privacy.

[1] The use of controlled entry technology in public libraries is also an equity issue concerning which groups of patrons can access the library outside of staffed hours. Who is excluded from the physical library in an open library model, and what are the implications of excluding them?

![A privacy setting option in the Overdrive App: "History - Display your borrowing history, with the option to add and remove individual titles. Learn more. [hyperlinked]"](https://ldhconsultingservices.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/SmartSelect_20210418-080304_OverDrive.jpg)